Blame is Easy - Accountability is Hard

4/30/2017

Some time back I was asked to come visit a winery that expressed an interest in adopting a Lean management system in their organization. I was excited to come see a larger winery in action, and took in every step of the process from crushing grapes to shipping final product with great interest. After all, I’ve been drinking wine ever since I was a kid at the dinner table (the product of a traditional Italian family) and now, here I was seeing a large-scale wine making operation in action. Totally different than what I saw farmers doing back in Italy 50 years ago! When in the bottling rooms, I witnessed all sorts of automated equipment with fork trucks coming and going bringing empty bottles to be filled and carrying pallets of ready to deliver product to the warehouse. The smell of wine and the clanking, and sometimes smashing, of glass was everywhere.

On the walls I saw Root Cause Corrective Action forms (RCCA’s). There were about 80 of them in various locations throughout the area. As I walked, I took mental notes of some of the detail on the sheets. Most of them had to do with defective products in one form or another. Notably the majority of them cited “Operator Error” as the root cause and “Re-Trained and Observed” checked off as the corrective action.

Later in the day I was asked to debrief with the executive leadership team on my observations of the day. I spoke about the value stream and areas where I could see a lack of flow as the product went from grape to bottle. Then I got to the defect rate for bottling and the RCCA’s on the wall. I pointed out that it was encouraging to see visual evidence of so many problems having been identified and resolved in a structured manner. Rather than accept the positive feedback their response was:

“Well yes we have a transient seasonal workforce. They are not all well-educated and there are at least four languages spoken in that area. We certainly have our challenges in getting everyone to understand how to do their jobs.”

So, I asked:

“Since we are discussing people,

Who hires these people?

Who trains these people?

Who manages these people?

Who owns the quality processes for this part of the process?”

Predictably I was not asked to return. Sad because this is one potential client from whom I really enjoyed getting samples!

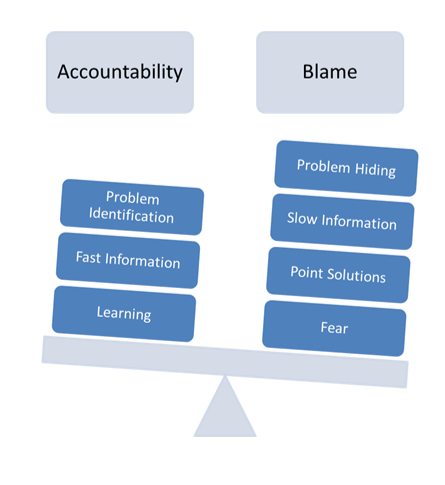

Accountability is a vital component of problem solving. However, blame is the enemy of problem solving.

But yet we have fallen into a pattern of interchanging those two words. We tend to say “accountability” but our actions speak “blame”. Accountable teams surface problems obsessively. Blaming organizations suppress problems out of fear. You never get to the first step of problem solving if you hide the problem.

In the book Extreme Ownership: How U.S. Navy SEAL’s Learn and Win, authors Willink & Babin provide examples of Navy SEAL teams in training doing poorly, and then, with only a change in leadership, making dramatic improvements. They speak of the burden of leadership being that failure always rests on the shoulders of the leaders. They posit that “there are no bad teams, only bad leaders”, and that successful leaders never blame their troops.

It seems as though each time I speak in a public setting about the true nature of accountability being the antithesis of blame that someone will fidget in their seat. After some time they will speak up in obvious frustration and say something to the effect of “well yes but sometimes you have to deal with the fact that someone is underperforming”. Yes, sometimes you do, but that’s not where you start. Before taking that route, you must examine the first principles over which your management system is built. If it’s built on first determining the “who”, then you will head down a path of results being associated with individual names. If it’s built on first determining the “how”, then you will head down a path of determining if there is a process, was it adhered to, and if so then is that process sufficient to get the intended result. Yes, sometimes you do have to sit down with an individual and explain that their performance is not up to par; that’s true even in a Lean management system. In fact, in a Lean management system, you are typically spending much more time discussing job performance and personal growth with subordinates than you would in a Management by Objectives (MBO) system. In MBO, all you have to do is measure results and the individual’s performance speaks for itself. The means by which the results, good or bad, are achieved is secondary. Leading with the understood eventuality of blame (or even credit for that matter) lingering in the air at each meeting leads to hiding problems. If, after assuring that your people are poised to succeed, (meaning that they have the resources, processes, training, and opportunity to do so), that you have tried problem solving coaching through humble inquiry, that the rest of the team is performing well, and that you’ve emphasized that options are running out for that individual, then and only then do you go down the path of “I’m sorry but you are simply not performing to expectations”. But recognize that that is far different than creating an atmosphere where negative repercussions are continually in the air. This eventuality should be such a rare event that it becomes painfully obvious to everyone that there was no choice. And yes….we still have to ask:

Who hired this person and by what process?

Who trained this person and by what process?

Who was leading this person and by what process?

Each of these questions should lead to further problem solving questions that strengthen the team’s ability to find and solve further problems. Remember the objective is to make the identification of problems and open discussion a desirable alternative.

In Extreme Ownership, Willink & Babin recount a story of the difficulty with successfully completing the Navy Seal team’s training. Teams are purposefully pitted against one another under incredible physical and mental challenges. In one story, teams carried large heavy inflatable rafts above their heads, while running along the beach, going through obstacles, and then paddling in the water, day and night, without sleep, for up to three days. One team consistently either won or came in second. Another team consistently came in dead last. The winning team would then be awarded a precious break from one of the evolutions. During one of the few and far too short rest breaks, the commanding officer announced that the leader of the winning and last place teams would swap places. The leader from the best team would now take over as the leader for the last place team. With no other changes other than the swap in leadership, the last place team started to come in near the top. The winning team started to fall behind. Same crew, same challenges, and identical training; all that changed was the leader and the management style that each brought to their leadership role.

The winning leader consistently encouraged his team. Not with fluffy “nice work guys, keep at it”, but rather by providing his team with specific short- term goals that gave them direct focus and provided them with immediate encouragement and satisfaction at each point of accomplishment. While running with the raft over their heads, he would find a feature on the ground, shout out how far it was, and encourage them to either push hard or pace themselves, as the case may be. With the team paddling in the dark of night, he would keep his eye on a marker on shore and keep the everyone apprised of their progress, all the while providing words of encouragement on their progress. The losing leader was more focused on how poorly his team was performing, rather than the process of leading and managing the team.

There was no change in team makeup, training, course terrain, or activity. The only thing that changed was the manner in which they were being led.

The restaurant industry has unfortunately made grand theater of how they manage their people. It’s a brutal environment with incredibly high attrition rates. While there are notable exceptions of well-run kitchens where voices are never raised and everyone is focused on their art, unfortunately the model of yelling and belittling junior help and wait staff is how the industry has defined itself. It’s become the stuff of reality TV shows. A very trendy two Michelin star West coast restaurant recently had one of their apprentices process 50 tangerines for a dish that the chef was going to prepare for a large party. The intern (read unpaid help) went in head first and did as he was told, eager to impress the chef. The problem became painfully obvious when the chef pulled out the tray of tangerines and he was a few short of the requisite 50 pieces of fruit. Under the pressure of getting the dish ready on time the chef yelled loudly “Can’t you count!? Are you an idiot!?”

Let’s dissect that for a moment. Not just the obvious part of public humiliation, but also the focus of the communication. “Can’t you count!? Are you an idiot!?” Not one word about process for this volunteering student of culinary arts who wants nothing more than to build his career around this experience. Understandably, getting the count right is important. There was a party of 50 people and missing one was not acceptable. That is indisputable and totally rational. But asking someone if they can count is not aimed at improving the process or the skill level of the individual. Of course, he can count and no, he’s not an idiot; only a hard working individual who idolizes the chef and is volunteering his time and labor in exchange for the opportunity to learn. The humiliation is only a relief valve for the leader who is frustrated at himself for not having yielded a better outcome. It’s quite probable that the chef’s leadership approach was the product of similar experiences he himself experienced while a student.

Another approach would be to mistake proof the process and ask the intern to lay out the tangerines in 5 rows of 10 on a cookie sheet, creating a visual that would prevent a miscount. Better yet, knowing that this was a new intern, he could have explained that we do it this way so that 1) there is no chance of a miscount and 2) it’s easier for me to prepare the dish when I pull it out of the refrigerator. In every aspect, the end result is better in the latter approach.

The intern would have likely learned something new, the chef gets what he needs to prepare the dish, and the whole team is much stronger after the fact.

This illustrates the differences between accountability and blame. One gives you a moment of satisfaction when you make sure the follower knows he screwed up. The other starts the thought process of “Because accurate counts are important, how can I get my counts exactly right each time while under pressure? What other ideas do I have?” This is how the “tricks of the trade” are born.

The burden of leadership is that one can never blame their subordinates. It is the leader who is not carrying out their responsibilities effectively. This is true of Navy SEAL’s, high end kitchens, factories, hospitals, insurance companies, and governmental agencies. It’s a universal principle.

It's not just blame…even crediting an individual by name can have negative consequences as well. Recall that Lean is Management by Means methodology which implies that every performance evaluation deals with both process and result. Never one over the other; they carry equal importance.

An insurance company established metric boards with performance measurements for each team. We generically call these ‘visual process performance boards’. In one underwriting department they had the weekly individual production numbers up by name. In the Friday meeting they congratulated the individual with the highest number for the week and handed him a $75 gift certificate as an award and the team applauded. We euphemistically called these awards “happy meals”. It’s actually a very effective reward mechanism as it really doesn’t cost all that much and the individual gets to take the prize home and relish a bit in their recognition with their family.

What could possibly be negative about this scenario? The numbers were objective and factual. No one could dispute those facts. Who would want to?

But no one talked about the process, only the results. That’s Management by Objectives, which is a different management system entirely. So what? It works, doesn’t it?

Well maybe…

Later we pulled up a few of the phone calls from this individual to try and discern what made him so much more productive than the rest of the team. What we discovered was that he was able to make his calls shorter by skipping some of the standard process steps. Rather than discussing potential additional coverage options, he saved time by simply checking off options that he “felt” the customer had a possible need for and never brought it up in the conversation. This caused a whole string of specialists to subsequently call the customer, trying to sell them additional coverage for which they had never expressed a desire. All of this resulted in annoying the customer and tying up staff with dead end calls. Not a positive outcome overall, but the individual was rewarded for the behavior.

How could this have been a better recognition process leading to accountability?

First, the leader could have done his Gemba walks and observed the process first hand before issuing an award. That would have caught the process drift early and prevented the problem from occurring at all. Observing the process directly is an indispensable component of Lean leader standard work. But it does take time and effort, and it can feel a bit intrusive. The Navy SEAL leader discussed earlier could not have achieved the success he did from a remote location by looking at performance results. He was right there with the team contributing in his capacity. As the saying goes ‘leadership is a contact sport’.

Secondly, and perhaps even more importantly, at this insurance company the team meeting was not poised as a learning event. It was more of a pep rally. The takeaway for the individuals on the team was “Get the highest productivity number and you will be congratulated, regardless of how you get it.” All that matters are results.

Lean is a management system which provides the environment for a learning organization. A more powerful alternative would have been to position the meeting as a learning session where the most effective processes are shared and the lessons learned are reflected back into the standard work. But the rub is that in order for the team to feel comfortable laying out their individual realities, they must not feel threatened by the management processes used by leaders. They must be energized by surfacing a problem and finding a solution…. Read “accountability”.

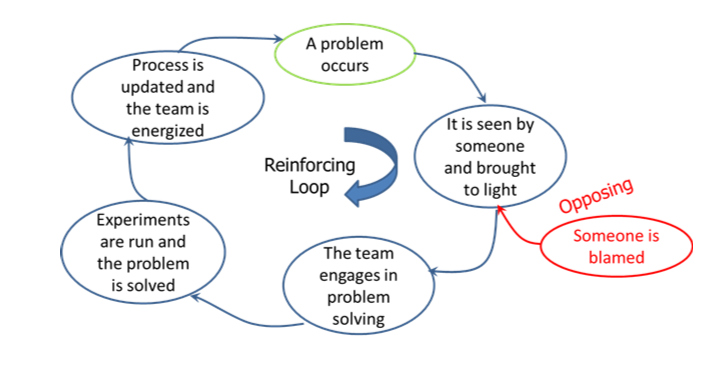

Blame begets more blame and problem solving begets more problems solved. A system dynamics view helps us understand these logic loops.

If a problem is discovered and negative consequences are observed by the team, fewer problems surface and fewer problems are solved. Alternatively, if a problem is discovered and the leader utilizes it as an opportunity to engage in a problem solving exercise, the team is energized, more problems are brought to light, and ultimately solved by the team.

Totaling the numbers up and blaming poor performers, or even crediting high performers is easy.

But figuring out how those numbers got where they are and having the entire team get excited over solving the problem and learn from the experience is hard. But that is the true nature of accountability

Joe Murli

What do you think?

Comments:

This post is more than 730 days old, further comments have been disabled.

Contact The Murli Group

Find out how we can help strengthen your company from the ground up»