What About Results? Isn't That the Point?

5/31/2017

Ninety years ago today, Henry and Edsel Ford drove the 15,000,000th Model T off the famed assembly line in Detroit Michigan. Yes, you read it correctly, fifteen million. Eventually, it became the 8th most popular car in history. Impressive, considering that Ford in many ways created the market for affordable cars.

No one can argue that Henry Ford was a very successful businessman. One of the tycoons of American history. He enabled the revolutionary transformation to individual high-speed transportation and established a legacy that is still a global force in the automotive world of today.

He is known today as a no-nonsense businessman. Not easy to work for. Marketing visionary. Constantly watching pennies so that the dollars would take care of themselves. He literally knew, to the penny, how much it cost to build each car. No one could claim to set more lofty objectives and be more results focused than Henry Ford. Not even to this day.

I’ve spent the last 27 years coaching organizations, speaking, and writing about Lean Management Systems. Especially on how process empowers people and the lack of process isolates individuals. Sometimes (often), in more public settings, the culture of Management by Objectives (MBO) is deeply entrenched and well-fortified by successful (even if sub-optimized) track records. It is hard, if not impossible, to ever change the thinking of one who subscribes to the school of “hire good people, align their incentives with the needs of the company, measure them often and with precision, and stay out of their way.” Its allure is understandable; you can’t possibly be everywhere all the time and it carries a façade of empowerment. Look at the Fortune 100 list of companies. It’s dominated by companies that manage under this set of beliefs. The ultimate evolution of the deepening MBO model is the “top 10, bottom 10” mechanism. By design, 10% of the lowest performing members of the workforce are fired and replaced and the top 10% are invested in and rewarded. What could possibly be a simpler or more elegant way of running a complex organization? It’s totally objective and self-correcting. Henry Ford was famous for firing people and there was a line at the front door of people wanting to work there. After all, it was the best paying job in town!

But there is a critical distinction. Mr. Ford was also famous for a much less common attribute among executives today. He constantly walked the line. His business model totally integrated the processes by which the customers’ needs were fulfilled. He was always looking for problems and waste in what was, in fact, the most efficient production line of its time. Nothing even came close to the efficiency of Ford’s business practices. He was the complete antitheses of the hire good people and stay out of their way school of management. He questioned every step of every process every day. Not just the assembly line. He questioned HR practices and how benefits were administered. When medical costs were viewed as out of line he designed, built, and operated a hospital. When he saw wooden crates being broken up and disposed, he redesigned the transmission shipping crates so that the wood could be reused for floor boards. The list goes on and on. It’s not that he didn’t have very talented people that he trusted. He brought Flanders in as the chief engineer to increase production rates to 10,000 cars per year and beyond.

But that never deterred Henry Ford, CEO, from walking the line, the Gemba, and finding problems. He never reached the point where he was too busy “running the business” to reflect deeply on the processes by which the business was run. But he never gave up walking the line and learning more and more about the process. To his way of thinking, that was in fact “running the business”.

Too often I see organizations initiate their Lean transformation efforts by designing and deploying metrics at every level and every corner; providing a line of site on important performance factors right down to every individual. Sure, the organizations get to the process soon enough, but at first, they want to be sure each individual knows how they are performing, how that contributes to the whole, and what the expectations are. The problem with this approach is that it causes people and processes to go underground. If production numbers are not met this week, that is a problem for sure. That would be equally true in an MBO as it would in a Lean Management System. No difference there.

The difference lies in the identification and solving of the problem.

- In an MBO culture, the problem is easy to identify, it’s “Jane”. The resolution is equally easy, Jane has to get on the ball and do what’s expected of her. There may be a process related problem, but since some others on the team manage to excel it’s not likely, is it?

- In an LMS culture, the problem is focused on the process and is harder to identify. It takes much more work to figure out “what do we know, what don’t we know, how can we learn the important factors that we don’t know”? There may be a bad actor responsible, but since the rest of the team is doing well, our people systems are probably working well and a bad apple is not likely, is it?

While both cultures seek to resolve the issue, the approaches to resolving the problem are very different from one another. And the solution that ultimately comes out of these approaches is likely also to be different. It’s not that you never have a process related solution in MBO, in fact, you often do. And it’s not that you never have a people problem in LMS, as that sometimes happens as well. It’s the direction from which you come at the problem and the infrastructure you build around the organization to facilitate the approach that differs.

In MBO you build a great deal of infrastructure around analytical and reporting mechanisms. Continually working toward more precise and granular data pointed at departments, teams, and individuals. People systems are focused on leveraging this information by providing clear carrot and stick incentivization to keep numbers on track. Processes are kept to a more general level so that people are “allowed to succeed” and excel without being hamstrung with really tightly controlled processes. Processes change slowly and are only changed after a great deal of review and only as approved by management. Those carrying out the process have less input into its evolution.

In LMS you build a great deal of infrastructure around process transparency and continual problem-solving. Continually working toward increasing the flow of value and making problems visible at the point and time of occurrence. People systems are focused on developing cohesive teams that are well aligned with company objectives. Processes are well defined as Standard Work and executed consistently from person to person. Small process changes are happening continually as problems are identified, controlled experiments are run, and solutions are put in place as new Standard Work. Those carrying out the process have a great deal of input into both its original definition and its ongoing improvement. The infrastructure is designed to facilitate rapid and pervasive change.

So here is the rub. In a Lean transformation, we spend lots of time developing processes and making problems visible. In fact, we spend so much time at thinking and talking out these attributes that the MBO thinker often jumps to a conclusion that LMS thinkers don’t care about results. They might possibly think that they are just Lean geeks that only care about the process without concern for the result. Those coming from an MBO world reporting up to MBO stakeholders will understandably lose patience discussing anything other than results.

The key is in the sequence in which we examine the business and what we measure. In daily operations, we want a balanced set of measurements that inform us when any aspect of the business is going astray. Only showing measurements that we feel are important because of today’s problems are the equivalent of a car that only shows the speedometer when you are speeding. Special measurements can be established as part of solving specific problems but once stabilized they should no longer be maintained. Let’s spend some time examining which result metrics we want to track in the daily management of a Lean thinking organization.

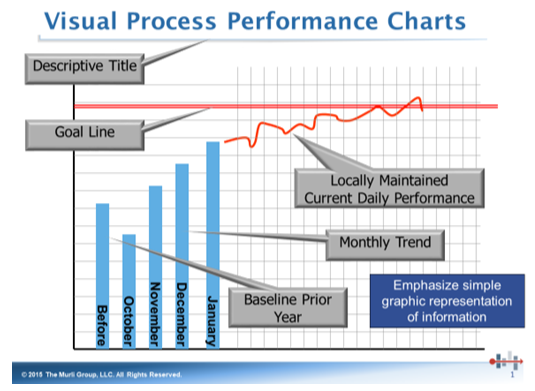

In order to measure performance in any category, some assumptions have to be determined for each case. Whether government, healthcare, banking, insurance, or manufacturing, understanding who the customer is, what the product (widget) is that you are providing, who the owners of the organization are and what is important to them are all important considerations. Keeping the metrics simple and approachable at the point of impact is as much art as science but the basic principles always remain the same.

- Descriptive title

- Goal line

- Baseline

- Monthly trend

- Current daily performance

It is useless to have a metric that is mathematically precise and procedurally correct if those doing the work can’t absorb it and act on it. The metric has to be a catalyst to action. And that course of action has to be deeper than simply making a specific number improve. The underlying purpose behind the number has to be served above all else.

Cost, of course, is always important. Unfortunately, the complexities of financial accounting which are optimized for external reporting sometimes make relevance at the point of impact difficult. The cost per good deliverable widget produced is crucial. Once you understand what your widget is, the challenge becomes defining which costs are most important in each team. The components of labor, material, and overhead change places from product to product. However, for each team in the value stream, one of these is the most controllable at their level and should be prioritized.

Service is very important in the mind of your customer. Giving your customer what they want, when they want it, in the manner in which they can best utilize it is key to customer loyalty and business growth. In some cases, loyalty and growth are not necessarily what you seek, as might be the case in a government agency that is responsible for providing their customers benefits. But even in these cases, service levels contribute to the overall value that those in need require to get their feet on the ground and what the shareholders (taxpayers) perceive as adding to the quality of life of their community. The cycle time from identification of the need to the widget actually being provided is central in this area of measurement focus. Some may say that on-time delivery is more important, and for sure meeting expectations are very important as well, but the shorter the cycle time, the more likely you are to be on time.

Quality is important, but not always for the reasons that are most intuitive. For sure, your customers want a high-quality product which meets or exceeds their expectations. But getting things right the first time is an indicator of overall waste in the system. Whether its internal first pass yield or external quality escapes, these metrics represent waste hidden in the system. The idea that improving quality increases cost is what almost killed the US auto industry, as Japan proved that theory wrong. There is no more efficient way to do the job than getting it right the first time. So first pass yield and customer escapes are two very important quality metrics

Now we are going to get into two areas of focus that are especially important to a Lean thinking organization, People and Continuous Improvement.

People are the only company asset which has the potential to increase in value over time. The rate of this increase is a direct correlation of the management system and quality of its leadership. So how do we measure how effectively we are cultivating our people’s skills and competencies? As the saying goes, “first do no harm”. Safety is always first and tracking injury rates and potential threats is foundational to this focal area. The next level up is skills and competencies development. There should be a clear set of developmental objectives for each team. If you are utilizing value stream mapping as a tool, then your future state map should include an identification of what skills and competencies you will develop over the next year. Your metrics should consequently track your progress against those objectives as part of your employee development plan. Finally, engagement is important to a Lean thinking organization. The days of good employees coming to work and doing what they’re told are over for Lean thinking organizations. We are asking everyone every day to find problems and work with their teams to solve them as part of their jobs. Tracking improvement in that area is key to measuring success in engaging the hearts and minds of the people. Thus, implemented ideas per employee is a key metric for tracking the rate at which leadership is building problem-solving muscle in the organization. The caveat of this metric is that leaders will have to be vigilant in making sure the ideas are actual ideas for improvement. Getting a dull tool re-sharpened or ordering new forms when running out are not ideas for improvement. Part of our Leader Standard Work is to look at the actual ideas that are being tracked and confirm their validity. That said, it’s a very powerful measurement of employee engagement.

Continuous improvement is our final area of performance focus. This is the most Lean thinking specific area of measurement of the five we are discussing. An indication that the pipeline of problems is flowing, that the deep thought and resolution of those problems is active, and that problem solving skill is continually deepening is what we seek in this area. A list of problems for the team to work on is created. One or more current A3’s showing the progress on the top priority problems and the tracking of problems that have been resolved are both necessary components to developing a composite picture on the CI portion of your metrics suite.

The balanced scorecard

- People

- Quality

- Service

- Cost

- Continuous Improvement

So why do Lean pundits get the bad rap of not caring about results, or at least not being focused on them? Well, messers Rockefeller and Ford would tell you that there is much more work to developing process. More detail, more people involved, more impact on infrastructure. Explaining how to put measurements in place really doesn’t take that long to explain by comparison. So, you are sitting across from someone that is explaining the Lean Management System. In a 60-minute conversation, 50 of those minutes are process and people related, and sprinkled throughout the conversation are several caveats warning you not to try to just measure your way to performance improvement. Then add to that additional warnings, that blaming people for shortfalls as the primary problem-solving method leads to people doing whatever is necessary to make their numbers look good, even at the expense of their peers and the customer. It’s an affront to the sensibilities of a seasoned, even successful MBO manager, and a natural response is to make assertions that personal consequence, both good and bad, is a vital component of business performance management.

No competent LMS expert would take issue that measurements are important, actually critical to success. In fact, in a mature Lean organization, measurements are everywhere at every level of the organization. They are posted visually at the place where the work takes place. But what is also pervasive are overt listings of problems, with teams actively working on them at every level. What is rare, not nonexistent but rare, is a closed-door performance review meeting one on one, where the boss is explaining that there is a problem and it’s the individual's inability to “make the numbers”.

There is a story about John D Rockefeller walking through the factory where his oil was being put in cans for shipment. Millions of Americans were lighting their homes for 1 cent per hour while making Mr. Rockefeller the richest man on earth. He had captured 90% of the refining capacity in America. The True North of the company would be paraphrased as “The best illuminator in the world at the lowest price.” In the midst of running this massive company, he paused and watched a worker soldering the vertical seams on cans, observing that 5-6 drops of solder would be deposited on the seam of each can. He asked the worker if he could try to solder a can with only 4 drops. Not 3 or 4 but exactly 4 drops. He did so as Rockefeller watched. The seam looked good, the can was pressure tested with success. A process was born.

Not just solder the joint and make a good tight seam, but rather solder the joint with 4 drops of solder and assure the seam is good and tight. The richest man in America had the time to do this at the Gemba. All the workers were trained and supervisors were shown the process to assure adherence to the process. The CEO of what was then the largest oil company on the face of the earth invested the time, emotional energy, and intellectual bandwidth to eliminate two drops of solder per can of oil. He was not too busy “running the business” to see how the business is run. He did not view it as “getting in the way” of the production manager or the craftsman to dig into that level of detail. On the contrary, he viewed this as displaying the management model that was expected at Standard Oil. Don’t just look at the numbers, understand how the work gets done, and always question it and look for problems to solve.

Not just solder the joint and make a good tight seam, but rather solder the joint with 4 drops of solder and assure the seam is good and tight. The richest man in America had the time to do this at the Gemba. All the workers were trained and supervisors were shown the process to assure adherence to the process. The CEO of what was then the largest oil company on the face of the earth invested the time, emotional energy, and intellectual bandwidth to eliminate two drops of solder per can of oil. He was not too busy “running the business” to see how the business is run. He did not view it as “getting in the way” of the production manager or the craftsman to dig into that level of detail. On the contrary, he viewed this as displaying the management model that was expected at Standard Oil. Don’t just look at the numbers, understand how the work gets done, and always question it and look for problems to solve.

The stories of these very successful businessmen have totally redefined their industries. Both committed to the idea that you can’t just manage results, but that a deep understanding of how that result is achieved is part and parcel of managing the performance of the organization.

Effective leadership is not about making speeches or being liked; Leadership is defined by results not attributes.

Peter Drucker

The “Practice of Management”

A treatise on MBO

A schematic of Management by Objectives

So were Henry and John Lean thinkers? Did they run their companies utilizing a Lean Management System? Well, almost. But one more evolution would be needed. In both cases, the process was “owned” by management. Workers simply did at they were told. To stray from the prescribed method, even if it was done with good intention was to risk your job.

Why is it that when I hire a pair of hands they come with a brain attached?

Henry Ford

A schematic of the Ford and Rockefeller approaches to management

While the ideas of strong processes and flow were solidly in play, enabling the entire workforce to engage in finding and eliminating waste was definitely not. With that let's move forward to Fugio Cho, chairman of Toyota Motor company.

Most of all you must learn to think for the company. That is my expectation for each of you. My job is to teach you how to do that.

Fujio Cho

Chairman Toyota Motor Co.

Comments at a new employee orientation meeting

People are the most important asset and the determinant of the rise and fall of Toyota.

Eiji Toyota

A schematic of the Lean Management System

That is where the difference exists. To be Lean is to say we are a culture of continuous improvement. In order to continuously improve in all corners of a complex organization, everyone has to be engaged, not just management. In order for everyone to be engaged, Leaders have to become coaches, building the problem-solving muscle of their teams. This doesn’t come by accident, nor is it easy. It’s not complicated, but it’s not easy. Every part of the organization has to align with the intent of engaging the hearts and minds of the entire organization to relentlessly find problems and fix them.

The achievement of an organization are the results of a combined effort of each individual.

Vince Lombardi

At times, we spend so much time talking about the methods of engaging people in continual process improvement that we forget the point of it all. It’s about results. But it’s not only results that matter.

The key is what end of the process you start from. Do you get it through the hearts, minds, and hands of your people, or do you roll over them to get the numbers? The answer depends on whether you want only a small subset of people solving problems or do you want everybody every day solving problems. The answer depends on whether you ask Cho or Drucker

What do you think?

Joe Murli

Comments:

This post is more than 730 days old, further comments have been disabled.

Contact The Murli Group

Find out how we can help strengthen your company from the ground up»