Lean Thinking In Government? Yes, But It is Different!

8/14/2019

What problem are we trying to solve?

In this day and age of hyper-partisan politics, it’s easy to overlook the fact that just below the surface of all the political rhetoric, we have over two million people working day to day jobs in the federal government. And that does not count all the state and local government employees. These are real people with families and aspirations who have chosen to make a career in government. Political leaders come and go with each election. But just below the level of those that influence policy decisions, there are hardworking career government employees that simply want to carry out their jobs.

The Lean Management System (LMS) places a hyper focus on two people in the value stream- the customer and those producing the goods and services that the customer seeks. But Lean has its roots in car manufacturing, so does it apply in Government work? As always, we start with the core concept of Lean being a collaborative, team-based, problem-solving system of management. So essentially, anywhere there are people producing a product or service for a defined customer, there is the opportunity to define and solve problems in the delivery of value to the customer.

The First Principle of Lean

That said, an automotive assembly line is a very different environment from a government office. Attempts to simply copy/paste Toyota’s solutions into Veterans Affairs, Environmental Protection, or Child Services agencies will not work. In some cases, you get local improvements, but over time they erode and you have difficulty gaining the buy-in from the teams whose hearts, minds, and hands you are seeking to motivate. Let’s look at those differences objectively and see their impact on how LMS is manifested in these environments.

Ken Miller provided a great service to all of us in the Lean community by defining a construct of government in his book “We Don’t Make Widgets”. Government agencies do in fact produce “widgets” even if they are not hard goods you can hold in your hand. A permit to allow a factory to operate its waste management system is one of many examples of a product produced by a government agency. The mission outcome of that permit is the economically viable operation of that waste management system in a manner that protects the environment within agreed upon (legislated) standards.

Government agencies also do in fact have customers. The factory manager seeking that permit is a customer. Perhaps one distinguishing factor in this case is that the customer often has no choice in doing business with the agency and therefore the motivation for quality and service may not be the same as in private industry where a company’s existence depends on customer satisfaction. This has implications on quality and service standards. If the permit is not actionable due to the way it’s written, the plant manager can not comply and society does not yield the benefits of environmental quality in balance with economic prosperity. Similarly, if obtaining the permit simply takes too long, the factory will have to shut down and send people home. This will likely lead to policy changes that support more timely services.

There are other more pragmatic structural differences between government and the more traditional organizations that have experienced Lean transformations, some of which are beneficial to Lean thinking and some of which we’ve developed countermeasures for. For starters, I have personally found that government workers by and large are highly mission driven individuals. Many of these people hold advanced degrees in their chosen fields and work for substantially lower wages than they could earn in private industry. They believe strongly in the importance of what they are doing for its own sake. But as is always the case, when faced with a process that doesn’t work, combined with an environment that makes it difficult or impossible to change the process, human beings will adapt. They will work around the system to achieve their outcomes and not be motivated to share those methods with others. Bottom line is that each person has their own version of the process working within the regulatory requirements of their agency.

Secondly, executive leadership vacate their positions to a pre-determined schedule. We live in a system of government where elected officials essentially are fired and have to re-apply (through re-election) for their jobs every four years, subject to term limits. Along with administrative changes, this brings with it a change-out of the policy making superstructure in the organization with every election. Over time this leads to an “Upstairs Downstairs” culture in most organizations whereby the owners of the estate live separate lives from those that maintain the property. But perhaps more the point, when teaching Lean Leadership Standard Work and Behaviors, coaches typically focus the bulk of their time with front-line and top tier leadership. Mid-level leaders largely develop through their interactions with the front-line and senior leadership. The planning for a transformation has to take this into account in order to avoid disruption over the next election cycle.

Additionally, a culture of compliance is part and parcel in working for the government. Policy is put forth, legislation is passed, regulations are written to operationalize the law, and the entire system is based on regulation, subsequently confirming compliance. It’s in the fabric of government in general. You get scolded for not engaging, but you get fired for being out of compliance, so the incentives are understandably significant. A focus on compliance can lead to an underdeveloped understanding of the “why” behind regulation that totally misses the point. Anyone who has been involved in Lean for a significant length of time can immediately see the differences between organizations that simply comply with their “XX-Production System” elements versus those that have really captured the culture of pervasive team-based problem-solving at every level. It is common for those working in government to first be concerned with complying with the letter of the law in any new requirement, leaving the intended outcome as a distant second.

So what does all this mean to those of us planning and managing a Lean transformation journey in public services? How do we adapt to what has been done since the early days of Lean at Toyota?

Let’s summarize:

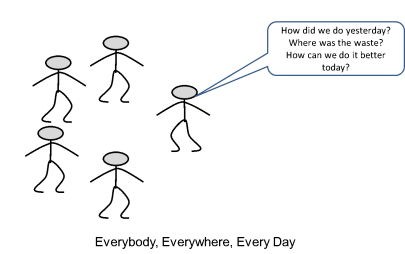

First, the product, or “widget”, is not always understood in clear, actionable terms. In business, as is true in government and life in general, we often get what we measure. When we start to think of our deliverable as a product, it influences how we measure performance. Metrics that clearly identify trends in lead time to deliver, quality performance in terms of first pass yield, and labor hour per unit delivered supports the discussion of what problems we see and how can we do it better today.

Secondly, the customer is also the person you are regulating. Clear leadership in this regard is a basic requirement. While the mission of the organization drives the quality of the product, managing any tendency for the conversation to drift off to “us versus them” goes a long way toward aligning the expectations of both the employees as well as the customer.

Thirdly, executive leadership transitions regularly. The countermeasure here is to re-distribute the hours spent training senior leadership in a typical manufacturing environment down to middle management. These are the people that stay behind as elected officials and their assigns move on to the next opportunity. Essentially you are capitalizing the “Upstairs Downstairs” phenomena to your advantage and galvanizing the changes that define your adoption of an LMS.

Fourth, compliance orientation demands very proactive work on the part of leadership. For every discussion on process, the leader’s dialog should include “How does this affect mission outcome”? When there are apparent conflicts, leaders need to be extra vigilant in practicing the Lean Leadership Skills to build structured problem-solving capability in their organization. How can we be compliant without compromising our mission and our customer?

Lastly, mission driven culture is the gift that leaders in a government setting have been afforded. While there are several areas where government agency managers have extra challenges as outlined above, this is a gift that many industrial managers wish they had. Most government agencies are filled with people who come on their first day extraordinarily committed to the agency mission and therefore True North is innate. This provides a consistent approach to the reflection process, which is the foundation of motivation for employees to adopt a culture of continuous improvement through problem-solving.

The bottom line is that Lean does work in government and works really well when done properly, with a focus on results rather than compliance. We have many examples from which to learn at this point, but just as is true in industry, copying one agency’s solutions into another’s does not lead to a Lean thinking culture. A Lean culture only works by embedding the problem-solving culture into all levels of leadership. The tools follow once the culture is adopted.

What do YOU think?

Joe Murli

Comments:

This post is more than 730 days old, further comments have been disabled.

Contact The Murli Group

Find out how we can help strengthen your company from the ground up»