The Andon- A Call for Help?

11/7/2019

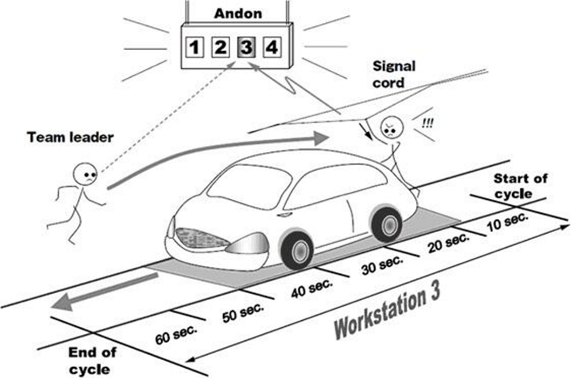

Hardly anyone who learns about Lean Management Systems hasn’t also been exposed to this iconic cartoon of a Toyota assembly line worker pulling an Andon cord and the supervisor immediately responding.

Courtesy Toyota Motor Co.

Courtesy Toyota Motor Co.

If we come at this from our traditional thinking, we interpret the image as one in which the supervisor responds to someone on the line who has a problem so as to help them get back on track. Pretty straight forward stuff at first glance. Right?

But there are layers of meaning here which reveal themselves as we look at the context within which this event takes place. There are several factors that enable this system to work that are totally invisible if you simply visit the factory and witness an Andon response in action. So lets dig into this a little more deeply than just what you see on a factory tour and examine how Andons can be adapted to your organization’s realities and become a vehicle for employee engagement and continual process improvement.

What is the problem we are trying to solve?

In most traditionally managed organizations, problems occur all the time in every corner of the enterprise, but most of those problems never see the light of day. Instead, those dedicated to doing the work to the best of their ability are motivated to work around those problems and keep doing their jobs. In fact, it becomes a point of pride that, despite all these problems, they can keep the ship moving forward. These are great people, dedicated to their jobs, and doing what they see as the right thing. Many businesses couldn’t operate efficiently without them. All too often their worth is only fully recognized when they retire and someone else has to take over their job!

To optimize our ability to continually improve performance, we need to fully leverage the eyes, heads, hands, and hearts of those doing the work at the front lines. There is no management team or IT solution that can possibly do a better job of this than those most directly connected with the work itself. We need to create an environment where the organization continually identifies problems, and announces those problems in an open and notorious manner. We then need to position our workforce to help solve those problems as they occur.

If we look at other problem-solving methodologies, such as statistical process control and Six Sigma, we see that analyzing the conditions under which a specific problem occurs is done by “experts” who are not directly engaged in executing the process. In my own experience using Six Sigma methods, I reflected on the reality that the bulk of my time was spent corralling all the parts involved in the nonconformance and then conducting the forensic analysis to help characterize the problem e.g. What material did we use? What shift was this part made on? Who was the operator? Which machine was used? What was the temperature in the shop when it occurred? etc. Once I had as complete a picture as I could build, I would develop a hypothesis and run experiments, measuring outputs very carefully and analyzing data until a link could be established between the process parameters and the root cause of the problem. This was all a very lengthy complex process that was managed by a Six Sigma technical specialist, in this case, me. By the way, my performance review, read pay, would hinge on the success of the solution, which is part of the Six Sigma process. Therefore, I was motivated to make sure I personally got credit for it, and that the credit wasn’t overly diluted with others that may have been (or should have been) involved. The whole affair was a lengthy complex process that emphasized the individual contribution of the specialist, and frankly alienated those actually doing the work. There were very few of these specialists, so only the highest priority problems based on financial impact drew attention. The mid and low priority problems could not ever possibly be addressed due to scarce resources.

What is the thought process inherent in the solution?

As an organization progresses in its adoption of a Lean Management System, it becomes more ingrained that engaging the hearts and minds of the front lines is central to its success and sustainability. If we set up those doing the work to instantaneously identify a problem at the moment it occurs, solving those problems becomes exponentially easier! The evidence is right in front of us and the circumstances under which the problem occurred are all there. This is not to say that you would never find occasion for utilizing the deep statistical tools of the Six Sigma discipline. In fact, the best Lean organizations have statisticians on hand. But the vast majority of problems are very quickly resolved with the involvement of the people at the front lines along with their direct leadership. So imagine an environment where many more problems are surfaced and many more people have the capability to solve those problems in far less time than it took before. That is what an effective Andon process enables an organization to do.

What are the missing components?

Why do we see so many organizations put up cords, lights, and buzzers and create a huge backlog of problems to solve? Eventually the Andon light goes dark and the cord gathers dust to become yet another monument to Lean gone wrong. Like so many other elements in Lean, there are environmental factors that have to be in place in order to make it work effectively. Ignore those factors and it simply will not work! In fact, you can do more harm than good and put yourself farther behind than when you started, rather than making progress.

Start with understanding what we are trying to communicate. When an Andon is signaled, what is being said to the organization is

Right here, right now, under these current conditions…

The process is not giving us the result we expect from it!

It is decidedly not “Hey I have a problem and I don’t know what to do!”

Or, “This has been happening on and off for a while now and I usually can work around it.”

Or, “I know this isn’t correct but I don’t want to get into trouble so I’ll hide it so no one sees it.”

The person pulling the cord may even know how to work around the problem or even fix it permanently, but they still pull the cord. The Lean Management System is a social and technical system. The social part consists of the cultural predisposition and the personal competencies to identify and solve problems. The technical part is the objective identification of an abnormal situation, the physical announcement, and the gathering of the immediate community to resolve it in a permanent manner.

What should it look like when in place?

An Andon call is a reflexive reaction, devoid of vague judgement, and as black and white as we can possibly make it. Notice that the cartoon at the beginning of this paper has elapsed time markers on the floor. This is a simple mechanism to take the judgment out of identifying a problem. It’s built into the process. This is the beginning of a process improvement cycle.

There are necessary environmental factors needed to make this messaging work:

- A clear and consistent quality standard that defines the expected outcome of the process. “What does good look like?”

- A standard work process. “This is the current one best way we have agreed on to carry out this work. And we will change it when we find a better way.”

- A training process that has been demonstrated to be successful. “I’ve executed the work as I was trained to carry it out. I wasn’t released to do this on my own until I could demonstrate proficiency.”

- An open and notorious method of notification. “Hey! Everyone around me. I’m signaling a process problem right here and now; my supervisor is on the way. We may want to discuss this in our next reflection meeting.”

- An enabling organization structure. “You signaled an Andon and I’m responding to you within our agreed upon time frame. Let’s deal with the urgency of the situation first and then do some structured problem solving!”

- Reflection. “Yesterday we had an Andon. Rhonda, could you please share with the team what we saw? What should have happened? What actually happened? What do we know? What don’t we know? How can we best learn those things we don’t know?”

- Experimentation. “Let’s use our capability to make temporary changes to the process. It’s called Moonshining and we can run a couple of controlled experiments to see if one of these ideas addresses the problem we observed.”

- Revised Standard Work. “We observed a problem, ran experiments, and have now modified our process. This is our revised Standard Work.”

- Lock in the gain and celebrate success. “We trained our workforce using our TWI methods and trained leadership in the new process. We monitored it for 30 days since completing all the training and have not seen a reoccurrence of the problem. Great work!”

So what?

While the principles are constant, the tools for each phase of the Andon are specific to the organization. What works well in one organization will be a total bust in another. Obviously, a Go-NoGo plug gage used to check holes in a machined part has no use in an office where air emission standards or veterans’ benefits are reviewed, or a clinic where medical procedures are being administered. While an automotive assembly line needs someone physically able to respond within 60 seconds, an office environment often can appropriately take as long at 24 hours, while in a hospital emergency room 60 seconds may be too long.

The organizational structure, including span of control, physical proximity to the workplace (Gemba), and working norms and culture, all must be aligned with being able to respond with proper timeliness and sense of urgency. Even within the same business we often have to make adjustments to Andon tools. A public service agency that has both rural and densely populated regions would likely not use the same processes for notification and response in each of these regions. However, the principles would remain constant throughout the entire agency regardless of the region in question.

People Systems have a great deal to do with the culture of an organization. Hiring practices, reward and recognition policies, and feedback mechanisms all have significant impact on an individual’s motivation to make an open claim to having produced a defect. In a Lean culture there is no room for the mindset of “I do my job so leave me alone.” Remember that this is a social and technical system and managers have to be equally prepared to deal with both of those areas.

The intent of laying all this out is not to scare you off as this being something too difficult to attain. It’s completely attainable. Many have done it successfully in a wide variety of environments. Implementation is a methodical step by step process that continually adds value to the workforce. As you progress, your people will increase their capabilities to become highly competent and engaged problem solvers. This ultimately leads to a world class standard of performance to which dedicated Lean thinking organizations strive and attain. Well thought out programs continually add value as they evolve. Haphazard implementation of tools on the other hand will almost surely lead to wasted time and resources, not to mention workforce alienation. We have all heard the adage of three steps forward, two steps backward. The reality is that doing this halfheartedly will lead to ending up further behind than where you started. If you’re going to do this, be committed to doing it correctly!

You can make mistakes, we all do, but you can’t leave the basic building blocks out altogether. Start in small areas and go deep. Build Standards, Standard Work, Training Processes, Leader Standard Work, Lean Leadership Behaviors. Then put Andons in place. Build on that foundation from there.

What do you think? I’d like to hear.

Comments:

This post is more than 730 days old, further comments have been disabled.

Contact The Murli Group

Find out how we can help strengthen your company from the ground up»